Hornbill calls heard again in Madyaas

Pandan, Antique -- The distinctive calls of writhed-billed hornbills are coming back into the deep forests of the Madyaas mountain ranges in Panay.

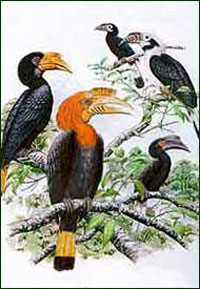

Colorful, playful and noisy, hornbills are among the most conspicuous local birds and were prominent in Filipino folklore.

They once inhabited most large Philippine islands during the Ice Age, with each island having uniquely colored hornbills each believed to be distinct species.

Today, the writhed-billed hornbill (Aceros waldeni) in Panay is virtually extinct.

The writhed-bill hornbill is listed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources as the world's second most threatened hornbill species. Others -- like the Visayan tarictic and the Sulu hornbills -- are critically endangered in most of the areas where they survive.

There are encouraging indications that hornbills forage once again high in the canopy of the deep Madyaas forests where the boundary of the four Panay provinces of Aklan, Antique, Capiz and Iloilo intersect.

In the Madyaas, hornbills hunt in small family flocks, noisily calling to each other as they spot food or potential predators.

"The forest of the Central Panay Mountain Range is the last refuge of the writhed-billed hornbill known to locals as dulungan," says Thomas Kuenzel, a German who manages the Philippine Endangered Species and Conservation Project (PESCP).

"And there it has survived with a substantial breeding population," he told InterNews&Features. "Whether that population size is viable is another question."

"From 2002 until now, there has been a steady increased of the number of nest holes occupied, from 31 to 502 nest holes in 2006," Kuenzel said.

"The enormous increase can be credited to the effective nest protection scheme. We believe that there are 44 percent increase of the number of nest holes this year compared from what we started with in 2002."

Former poachers and hunters have been signed up as "owners" of 132 nest holes that they are sworn to protect. The network also includes six wildlife educators, 17 community conservationists and 14 barangay tanods serving as the community police.

"This network of conservation workers is supported by livelihoods planned and implemented together with the communities living in an around the forest inhabited by the hornbills," Kuenzel said.

Hornbills are so-called because the bills of these birds are enormous and usually brightly colored. The top of the bill is a hollow structure called a casque that serves as a resonating chamber for the bird's calls.

Hornbills eat a wide range of foods -- including mice and nestling birds -- but depend on wild figs in old-growth lowland rain forest.

They live for as long as 20 years and, like most large birds, reproduce very slowly and take great care raising their young.

When the female is ready to lay eggs, the male brings mud that the pair fashions into a solid wall covering most of the opening into their tree-hole nest. The female stays inside the tree-hole to incubate the eggs and nestlings until the young are ready to fly, entirely dependent on her mate to bring food for herself and their brood.

Because they reproduce slowly, writhed-billed hornbills are generally unable to survive heavy hunting. Logging exerts its pressure, denuding lowland rain forest of the trees that provide nest holes.

In 2002, it was estimated that half of the writhed-billed hornbill population in Panay was lost to poaching.

That was six years after Eberhard Curio, a retired professor at Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany, founded the PESCP together with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

Starting with a small presence here, the group encouraged upland barangays to protect the writhed-bill hornbill. The word has spread from just five towns to 35 barangays in the 12 towns of all four Panay provinces that border each other in the Madyaas.

With such encouraging developments, Kuenzel is confident that the Madyaas forests will continue to echo with the calls of the hornbills.

InterNews&Features